Outgrowth of the Lighthouse Keeper: USCG Aids to Navigation Teams

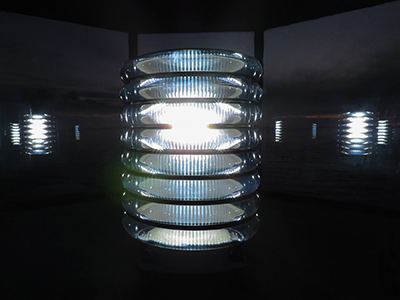

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

Lighthouses and their keepers are inseparable – and always will be as long as they continue to stand, shine bright and bellow out their audible warnings into the future to come. For no matter how many advancements in technology are achieved, the lights – to this very day, still require dedication, skill, a keen eye and human hands to keep them watching properly.

It is widely regarded that the golden era of lighthouses ended when automation banished the lightkeeper from the confines of our sentinels of the sea. In Maine, the automation process gained momentum in the 1960s and this altering “wave” did not crest over the seascape until the last Coast Guard keeper – Bradley Culp, was removed in 1990 from Goat Island Light, Cape Porpoise.

(Dominic Trapani photo)

But did lighthouse keepers ever really go away or did their role simply evolve with progress upon the tides of time? It depends on your perspective. In a traditional sense, yes, keepers have disappeared from our lighthouses. Yet, if one considers the function and not the form of lightkeeping, then the essence of keeping a good light continues to shine bright here in the twenty-first century.

For sure the concept of keepers and their families residing at the lights on a daily basis and caring for the station buildings and grounds was lost to automation. But no self-operating lighthouse system this side of artificial intelligence can fully eliminate the need for a niche group of well-trained and talented individuals to keep things running smoothly.

This is what makes United States Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Teams so vital to our lighthouses today. They serve as the modern day “wickies” who trace their roots back to the founding of our country.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

“Managing the nation’s aids to maritime navigation is in fact the earliest mission of the Coast Guard, as this mission officially began on August 7, 1789, when Congress agreed to accept control of the nation’s lighthouses that had previously been established and run by the Colonies,” said USCG Lieutenant Katie Braynard in a June 2015 article entitled, 225 Years of Service to Nation: Aids to Navigation.

With the relentless march of time, lighthouse keepers eventually gave way to keepers of the lights in the form of U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Teams (ANTs). In fact, the two (lightkeepers and ANTs) overlapped in Maine for nearly a quarter century (1976 to 1990).

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

During this time period, the 1981 USCG Aids to Navigation Manual touched on the evolution of lightkeeping, stating, “An ANT is essentially an outgrowth of the light attendant station. An ANT will generally have more personnel and equipment than a light attendant station, and will be responsible for servicing more aids.”

When ANT’s were originally created to service lighthouses and other short range aids to navigation, they ranged in size from 4 to 27 personnel. In contrast, an offshore light station was composed of 3 to 5 Coast Guard keepers, with at least two on site at all times.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

The 1981 manual went on to note, “The Coast Guard has been in the process of unmanning lighthouses ever since the responsibility for operating 503 lighthouses was assumed with the transfer of the Lighthouse Service in 1939. Due to the high cost of maintaining isolated manned units, lighthouses have been converted to unattended operation.”

Initially, as lighthouses were converted to automatic operation, the care of the light station and its equipment was delegated to the crews of inshore and seagoing Coast Guard buoy tenders, and some search and rescue stations as well. Though the crews afloat did an admirable job, it was clear that a new system was needed for the long term to ensure the lights and their operating equipment were provided the most cost efficient, prompt and expert care possible.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

Rear Admiral Richard Bauman, Chief, Office of Navigation, U.S. Coast Guard, astutely noted in the early 1980s that “Servicing aids to navigation demands a mission dedicated force. The work is technical in nature and must be mastered.”

By the mid-to-late 1960s, many buoy tenders were at an advanced age, while the Coast Guard was also incurring high annual costs with efforts related to servicing aids. In addition, Congress was seeking answers as to ways the USCG could reduce costs with the military organization’s overall budget. In light of the operational and financial challenges associated with aids to navigation, Coast Guard leadership set out to find solutions by partnering with the management and information technology consulting firm, Booz Allen.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

According to the Historical Summary of Aids to Navigation Analyses, Volume I, April 1998 by the U.S. Coast Guard Research and Development Center, “The Coast Guard formed a National Navigation Planning Staff that managed the Booz Allen study, which was completed in 1970. The Booz Allen study is a landmark in aids to navigation planning since it represented a departure from the incremental efforts that preceded it. Booz Allen took a systems view of aids to navigation and developed an integrated proposal for the service force mix.”

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

The study went on to say, “A new service element was proposed: the Aids to Navigation Team that would be equipped with special aids to navigation boats or trailerable aids to navigation boats. Booz Allen identified a complete mix of shore facilities that would be required to support the servicing effort. The major cost reduction came with reducing the number of offshore and inshore buoy tenders associated with changes in servicing schedules and the use of dual responsibility for aids.”

In the 1971 Coast Guard Bulletin, Lieutenant R.F. Doughty from Coast Guard Headquarters, stated, “Since the ANT will not be assigned responsibility for any other missions, all servicing functions will thus be conducted by trained personnel working full-time on aids to navigation. Therefore the servicing will be done by people dedicated to the ATON mission and fewer discrepancies and a more effective aid system should result.”

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

In the wake of this historic study and its visionary recommendations, a quote from the 1955 book Keepers of the Lights by Hans Christian Adamson seems appropriate. At the time, the author said, “There is a cost, a price, attached to everything. With respect to our lighthouses, lightships and other aids the price has been the foregoing change in emphasis. It is no longer the keeper and his light. Now it is the lights and their keepers.”

The National Navigation Planning Staff was subsequently disestablished with the completion of the Booz Allen study and it was now time to create Aids to Navigation Teams. This responsibility was assigned to the Coast Guard’s Aids to Navigation Division.

The pilot program called for the first ANT to be field tested in New Haven, Connecticut in 1972. The newly created ANT, called ANTEVALUNIT New Haven, was a resounding success, and by 1973, the Coast Guard began to strategically establish ANTs around the country.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

During Congressional Hearings before the Subcommittee on Coast Guard and Navigation of the United States on September 22, 1982, Rear Admiral Richard Bauman, stated, “The first aids to navigation team was established in 1973, and a majority of the aids to navigation teams were established in the 1973-76 period.”

When Senate and House committee members asked to confirm that the purpose of creating ANTs was to make a substantial improvement in efficiency, Rear Admiral Bauman replied, “Yes, sir. With the teams located in the geographical area, they were able to provide rapid response and also very specialized service for that group of aids that they were responsible for. And in doing so, eliminate the need for as many larger vessels.”

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

According to the September 1993 Overview of the U.S. Coast Guard Short Range Aids to Navigation Mission, “The number of ANTs escalated from nine in 1974 to 67 in 1980. During the 1980s the number stabilized and today, 64 ANTs service over 36% (17,700) of all ATON.”

Though this feature focuses on the role U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Teams play in the area of lighthouses, make no mistake about it, ANTs do far more work than what is associated with ensuring coastal sentinels “wink & blink.”

In fact, truth be told, lighthouses are but a small part of the ANT’s overall mission. ANTs also maintain minor lights, daybeacons, electronic aids and a plethora of buoys.

(Ann-Marie Trapani photo)

So though the Coast Guard could demonstrate to Congress tangible cost savings with ongoing efforts to automate lighthouses and via the creation of Aids to Navigation Teams in the 1970s, they also realized significant cost savings by implementing other recommendations from Booz Allen. These included changing from a two-year to a six-year buoy relief cycle, annual to biennial buoy mooring inspections, and semi-annual to annual daybeacon/light/buoy inspections.

If we look back through the annals of lighthouse history, hindsight reveals the fact that the irresistible lure of technology was always enthusiastically embraced by those who had oversight of America’s lighthouse system. Greater effectiveness and efficiency were relentlessly pursued, and eventually, improved to levels that lessened further and further the need for constant care by onsite keepers.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

By 1915, the United States Lighthouse Service was integrating technology at a more rapid pace. Though it did not have a noticeable impact on the role of traditional lightkeepers at the outset, the organization’s focus on the latest science had to offer undoubtedly began to pave the road to automation.

A few examples include:

1915 – Temporary unwatched gas lights tested.

1916 – The first flashing acetylene lights and devices for automatically replacing burned-out incandescent electric lamps deployed.

1917 – Thermostat-sensing equipment for oil-vapor lamps and lighting equipment for post lanterns that could automatically occult were established in aids.

1921 – The first radio fog signals in the country were installed.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

1924 – A tube transmitter for radio fog-signal stations was used.

1928 – The first automatic operated radiobeacon was placed into operation.

1929 – The first synchronized radiobeacon and air fog signal with electric oscillators were deployed.

1933 – Range lanterns utilizing compound lenses and 4-volt miniature lamps, operating on primary cells with photronic cell control were placed into service.

1934 – A lightship was equipped for remote control operation of all its facilities as an unwatched aid, including its light, fog signal and radiobeacon.

1936 – A battery-operated electric solenoid-operated fog bell striker of the clapper type was experimentally installed.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

1937 – Experiments to test the use of remote control apparatus for fog signals by means of a modulated light beam (essentially, the first fog detector) were made An article entitled, Automatic Lighthouses Save Money appeared in the September 1, 1925 edition of the Lighthouse Service Bulletin. In the article, it is stated, “The total number of automatic lights in commission on fixed structures of June 30 last was 993.” The feature later noted, “Commissioner Putnam estimates that the automatic apparatus now in service does the work of over 800 light keepers.”

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

Of all of these (and more) technological advances in the field of lighthouses and aids to navigation in the early twentieth century, arguably, the most groundbreaking technology deployed by the United States Lighthouse Service was the radiobeacon. One perspective of the radiobeacon’s legacy is to view its accurate radio-direction finding capabilities during all types of weather conditions as the forerunner to today’s digital electronic navigation equipment. At the time, no light or horn at a lighthouse could match the radiobeacon’s long-range and precise navigational signal.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

In his 1997 book Lighthouses & Keepers, author Dennis L. Noble stated, “By 1924, the U.S. Lighthouse Service was the largest such agency in the world with 16,888 aids to navigation. Interestingly, while the aids to navigation had more than doubled, the number of employees had decreased by nearly 20 percent. The reason for the decrease in personnel was due in large part to the adoption of technological advances, such as the use of electricity that reduced the number of people needed to attend the lights.”

Dennis L. Noble concluded, “Technology would have great consequences for the future of lighthouses in the United States.”

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

The June 1939 Lighthouse Service Bulletin contains a quote by U.S. Lighthouse Service Commissioner Harold D. King that eloquently captures the spirit of keeping pace with science and technology. According to Commissioner King, “…progress is also a fundamental characteristic of the work of the lighthouse keeper and the lighthouse engineer, and the advance and development of the race in civilization comes not through the changelessness of either organizational forms of society or of lives of individuals but through progressive regeneration.”

The United States Coast Guard has continued this longstanding tradition of integrating the latest in light and sound signal technology in our nation’s lighthouses.

Today in the State of Maine, there are two U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Teams – one in South Portland and the other in Southwest Harbor. These two hardworking units are largely responsible for making sure the Pine Tree State’s 55 federally active lighthouses send out their guiding gleams each and every night, and the 37 active fog horns sound effectively on demand.

(USCG photo)

The Coast Guard’s 65-foot cutters BRIDLE, TACKLE and SHACKLE also lend a hand to the task of keeping a number of solar powered lighthouses watching properly in Maine. Even U.S. Coast Guard Air Station Cape Cod plays an important role by providing air support to both ANTs when it comes to servicing a number of wave-swept, offshore lighthouses.

As is always the case with any successful mission, teamwork is the key!

So what do Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Teams do today?

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

As for lighthouses, whereas the keepers of old tended to the lights on a daily basis, modern U.S. Coast Guard lighthouse technicians service the beacons and horns on a quarterly, semi-annual or annual basis, but tend to them they still must do to ensure the mariner can confidently rely upon them when needed. The servicing interval is largely determined by the light’s power source and overall complexity of the onsite aids to navigation equipment.

During these visits, lighthouse technicians will thoroughly inspect the main and secondary (where applicable) optics, verify the beacon’s characteristic and check over all of their associated electronic navaid support equipment. In legacy optics, spent lamps are replaced and lampchangers, flashers and daylight control units are tested. If the optic is a light emitting diode (LED) beacon, technicians will test its daylight control unit and confirm its flash characteristic for accuracy.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

Lighthouse technicians will also test the sound signal’s components and its Mariner Radio Activated Sound Signal system, ensuring the mariner can activate the horn on demand during foggy or thick weather.

In addition, photovoltaic systems are examined and tested, batteries are serviced, and cable runs and connections are inspected. Any required corrective and/or preventative maintenance is carried out during these visits to ensure the light and sound signal are watching properly upon departure.

When a beacon is reported extinguished or a sound signal is discovered inoperable, ANT personnel repair the discrepancy in a timely fashion.

(Dominic Trapani photo)

In the world of lighthouses, it seems as much as things change, they remain the same. Akin to the days of yore, it is still all about keeping a good light. This fact serves as a reminder to sentiments expressed by United States Secretary of Commerce Daniel C. Roper, who served under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. While addressing U.S. Lighthouse Service leadership in 1938, Secretary Roper stated, “You must maintain the lamp in the window for those who would find the way safely among the difficulties of the sea.”

Present day U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team personnel keep this concept alive and gleaming. The passage of time and society’s technological advances have not dulled the zeal of Coast Guard keepers of the lights when it comes to perpetuating this time-honored command.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

Spend any amount time around a U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team and it becomes quickly apparent that the crews hold in high esteem their lightkeeping roots and America’s rich lighthouse heritage in general. ANT personnel are keenly aware of the fact that their work directly connects to our lighthouse past and the keepers who served before them.

Honor and respect for tradition is as important as skill and achievement to Aids to Navigation Teams. By knowing where lighthouses have been, modern day keepers of the lights are able to help steer the future of our sentinels as functioning aids towards bright horizons.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

In 2020, the Coast Guard still maintains 64 aids to navigation teams around the country. These dedicated units are a big part of keeping over 1,000 harbor channels and 25,000 miles of coastal waterways safe for commercial shipping and recreational boaters alike. In all, the Coast Guard maintains nearly 50,000 aids to navigation nationwide.

“Waterborne cargo and associated activities on the navigable waterways component of the Marine Transportation System contribute more than $649 billion annually to the Nation’s gross domestic product in personal wage and salary income and local consumption expenditures, sustaining over 13 million port-related jobs, said USCG Lieutenant Katie Braynard. “In addition to waterborne cargo, nearly 73 million U.S. citizens are involved in recreational boating, international and coastal trade, and marine fisheries, all of which contributes $70 billion annually to the U.S. economy.”

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

Author Hans Christian Adamson aptly sums things up in relation to lighthouses and their keepers by saying, “The story of the lights is complicated by its many aspects. It is not a simple one-track saga of devices that changed with the march of time. It is, rather, a biography of the human effort, courage and sacrifice that have gone into the keeping of the light.”

U.S. Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Team personnel continue to exemplify these noble sentiments in the 21st century. If lighthouses still shine – and they do, then someone must keep them gleaming without fail.

(Bob Trapani, Jr. photo)

Regardless of one’s perspective on how lighthouse keepers and keepers of the lights are to be viewed by history, one thing is certain – human hands are still required to help keep those at sea safe. If, in pondering the essence of our lighthouse heritage, it is to be determined that a guiding light over a dark and treacherous sea remains the most benevolent of duties, then tradition remains unbroken to this very day thanks to dedication and hard work of United States Coast Guard Aids to Navigation Teams – Keepers of the Lights!

This story originally appeared in the February/March 2020 edition of Maine Lights Today magazine.