The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lantern Pane Duties

(American Lighthouse Foundation archives)

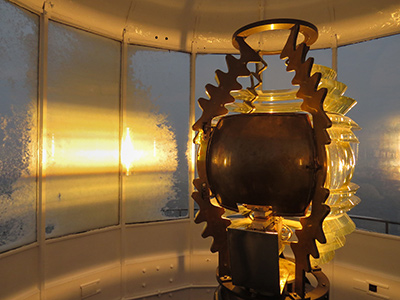

Looking back through lighthouse history, you might say that keepers were very good at cleaning windows. Maybe not by choice, but duty called nonetheless. When it came to the panes of a lantern, keepers were instructed to diligently remove any dirt, soot, condensation, frost, ice or drift snow that might accumulate upon the surface of the glass during the light’s hours of operation. This included both the interior and exterior panes.

According to the 1870 United States Light-House Board Instructions and Directions to Guide Light-House Keepers and Others Belonging to the Light-House Establishment, “The plate glass of the lantern must be kept at all times during the exhibition of the lights entirely free from dampness or moisture by frequently wiping it off both outside and inside with clean, dry towels.”

The instructions went on to say, “During stormy and thick weather light-keepers are required to give their whole time and constant attention to the lights in their charge; to keep the flames at their greatest attainable height, burning brightly and steadily, and the lantern-glass free inside and outside of moisture. During heavy gales of wind, snow, rain, and hail storms, the lights must never be left unattended by a keeper.”

(Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.)

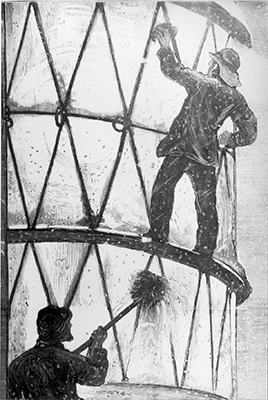

Under no circumstance could the guiding beams shining forth from a lighthouse be reduced in intensity, or worse, altogether obstructed, by such impediments. No matter the hour of the day or the fierceness of the elements, keepers were required to venture outside onto narrow, wind-swept galleries numerous times during a single weather event to clear the panes. Few keeper duties proved to be more dangerous.

The mere act of walking around a circular gallery into the face of a furious gale could be physically challenging at best, and hazardous to one’s safety at worst. The threat of being swept off the lantern gallery was very real when the wind was blowing great guns.

(Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.)

With one hand strongly gripping the gallery railing and the other trying to maintain a firm hold on the glass-cleaning tool of choice, the keeper would pull himself along with great exertion until he arrived at the windward lantern panes.

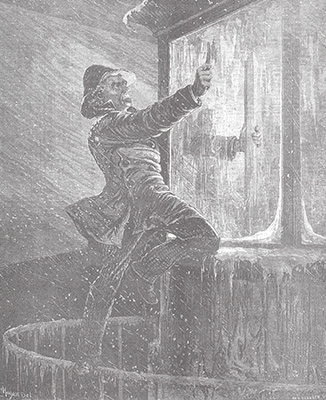

Typically during a raging snowstorm, three or four lantern panes on the windward side were the ones most adversely impacted by accumulating snow. To properly remove the snow from the entirety of the glass surfaces, keepers would often need to boost themselves up onto the icy gallery railing to reach the upper parts of the panes. Even if the lantern had hand-holds to grab, this action required every ounce of caution, strength and guts as a pitiless wind galloped by the lighthouse unrestrained.

(Harper’s Weekly image)

No sooner would the keeper sweep away the obstructing snow or ice and retreat to the protective confines of the lantern, the frigid impediments would begin gathering in blanket-like fashion once more. Blizzards had to be the most taxing of times for keepers trying to maintain a clear path for the light to shine seaward.

Light stations with more than one keeper often fared better than stations with one keeper during such stormy times. Under the heading of “Cleaning the snow, ice, frost &c., from the plate-glass” in the 1870 instructions, the Light-House Board stated, “For the more effectual removal of snow, ice frost and wet from the plate-glass of the lantern, which may have accumulated in the day, during the winter period, from October 1 to March 31, two keepers must go and remain on watch throughout the first hour, from half an hour before until half an hour after sunset, one to perform all the duties connected with the apparatus, lighting the lamp, regulating the height of the flame, the damper and ventilation; the other to remove the apparatus cover, take down the lantern curtains, and return the oil carriers and other utensils to their proper places, &c.”

(Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.)

The instructions went on to say, “The journal of the light station must show that these double watches are regularly kept from October 1 to March 31, and by whom, on each day during that period of time. The keepers in charge of the lights, after the expiration of the double watch, are required to remove all accumulations of drift snow, sleet, ice, and frost from the outside, and to remove all moisture that accumulates on the inside of the glass of the lantern.”

As challenging as fast-accumulating snow or sleet upon lantern panes could be, the most dreaded obstruction was freezing rain. The instant freeze of the falling rain upon cold glass surfaces could create an opaque crisis real quick for keepers. Clearing any thickness of ice from the panes was not only a tough job, but rarely was the cleaning process initially uniform. Scraping the same area over a number of times to remove stray streaks of ice could easily be required. In addition, the keeper also had to be mindful of not cracking the glass panes as he worked to clear the icy obstructions.

(Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.)

Though the threat of lantern panes becoming obstructed during storms could not be eliminated, the Light-House Board did provide the keepers with at least a helpful option to reduce the adverse effects. According to the 1870 instructions, “When ice, sleet, or drift-snow settles on the outside, or when the ice forms in cold weather on the inside of the glass of the lantern, a strong brine applied to it will remove it without difficulty, and, in extreme cases, a small quantity of spirits of wine may be employed with advantage for the same purpose.”

(Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.)

Keepers were also provided with extra panes of glass in the event that storm conditions or light- blinded birds crashing into the lantern caused a pane to break. These situations were thankfully rare, but when they did happen, the Light-House Board was pretty direct in their instructions. The spare panes had to be “kept at hand ready for instant use,” and the repairs had to be made “without unnecessary delay.” Just how a keeper was to repair a broken pane in the middle of raging rain or snowstorm was not expressed…it was just expected.

(Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.)

Over the years, the author has had the experience of being inside and outside the lantern of Owls Head Lighthouse during many a storm. Watching the snow accumulate along the windward panes in real time gives one a new perspective as to some of the challenges bygone lightkeepers faced. And then there is the wind, which does not change. The wind is quite a foe to contend with when simply walking around the gallery—let alone trying to carry out a task in the face of its relentless buffeting.

(Photo by Bob Trapani, Jr.)

When it comes to our lighthouse history and the duties associated with keeping a good light, clearing the lantern panes during all types of moisture-laden weather may very well be one of the more underappreciated tasks performed by lightkeepers. For it was during stormy weather when mariners needed the light most.

In the end, thick weather may have reduced the range of the guiding gleams out at sea during a storm, but the dedicated keepers of old did their part to at least make sure that the beams of light were sent forth from the lantern in the most intensified fashion possible. In doing so—all the while risking their own safety as they carried out this vital task, who knows the number of untold lives that were saved by such faithful duty. As a keeper might say, “it was all in a day’s work.”