Aberrations of Audibility of Fog-Signals

The following information about oddities related to fog signals was published in the government publication, The Modern Light-House Service, 1890, by Arnold Burges Johnson, Chief Clerk, United States Light-House Board.

(Maine Lights Today archive)

“Among our erroneous popular notions is one which occasionally brings practical men, even ship-masters, to grief. It is the idea that sound is always heard in all directions from its source according to its intensity or force, and according to the distance of the hearer from it. Instances of this fallacy have accumulated, and they are emphasized by shipwrecks caused by the insistence of mariners on the infallibility of their ears, who have accepted unquestioned the guidance of sound signals during fog as they have that of light-houses during clear weather.

“The fact is, audition is subject to aberrations, and under circumstances where little is expected. We have learned by sad experience that implicit reliance on sound signals may, as it has, lead to danger if not to death.

(Later) “The Board’s publications show that Professor (Joseph) Henry, its scientific advisor, had the subject for many years continuously under advisement, and that between 1865 and 1878 many experiments were made, and various reports on them submitted to the Board as to the use and value of its several kinds of fog-signals.

(U.S. Lighthouse Society photo)

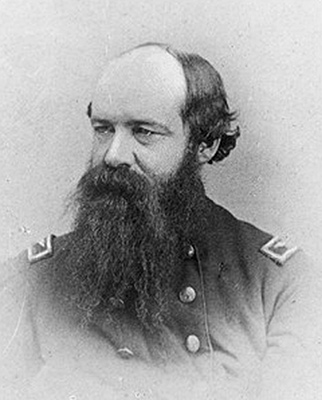

“In 1870 the Board directed General (James Chatham) Duane, of the U.S. Engineers, to make a series of experiments to ascertain the comparative value of its different signals. In his report the general said, speaking of the steam fog-signals on the coast of Maine:”

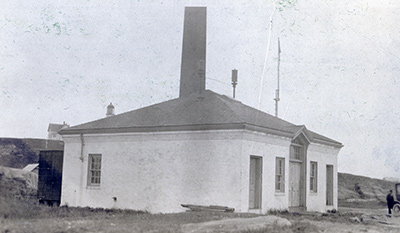

There are six steam fog-whistles on the coast of Maine; these have been frequently heard at a distance of 20 miles, and as frequently cannot be heard at the distance of 2 miles, and this with no perceptible difference in the state of the atmosphere.

The signal is often heard at a great distance in one direction, while in another it will be scarcely audible at the distance of a mile. This is not the effect of wind, as the signal is frequently heard much farther against the wind than with it; for example, the whistle on Cape Elizabeth can always be distinctly heard in Portland, a distance of 9 miles, during a heavy northeast storm, the wind blowing a gale directly from Portland toward the whistle.

(National Archives photo)

The most perplexing difficulty, however, arises from the fact that the signal often appears to be surrounded by a belt, varying in radius from 1 to 1 ½ miles, from which the sound appears to be entirely absent. Thus, in moving directly from a station, the sound is audible for the distance of a mile, is then lost for about the same distance, after which it is again distinctly heard for a long time. The action is common to all ear-signals, and has been at times observed at all the stations, at one which the signal is situated on a bare rock 20 miles from the mainland, with no surrounding objects to affect the sound.